The Five Misconceptions about Communication

Using the principles identified above as the foundation for generalization about the nature of communication, it is possible, therefore, to identify conclusions and or claims that are at variance with the stated principles. Consequently, these general misunderstandings about communication, we can reason, are common claims that go against the established truths about the nature of communication. The insights that they reveal will open the eyes of the student to in-depth theoretical thinking that is necessary to grasp what a people perceive to be a rather easy to understand phenomenon.

Communication Will Solve All Problems

Understanding the communication principles outlined and discussed earlier should give us an insight into the world of communication as a rather complex and nebulous thing that can aid us in many ways and that can be a source of problems to us. But many people attribute magical powers to communication and they see and act as if it were the panacea to all human problems. Often you hear people say that: “if we communicate and understand each other’s points of view, we will resolve our conflict or problem: While I may understand your point of view, but it is exactly that point of view that may be the cause of the problem.” As aptly put by Seiler and Beall (2011), the act of communicating with others does not carry any guarantees. Obviously, without communication, we cannot solve our problems, but sometimes communication can create more problems than it solves. This fact leads us to the next misconceived idea about communication.

The More the Communication the Better

I have a saying to my students and clients – “More communication isn’t better. Effective communication is better!” The fact that you do something repeatedly does not mean it is right. If you repeat the mistakes of the past over and over, that, certainly, would cause more harm than good. As an avid golfer, if my son kept repeating an ineffective swing in thinking that practice makes perfect, what he is clearly doing is learning, and ingraining, something that will produce an ineffective result. Effective and competent communication is a result of doing more of the right thing at the right time, to the right person, and possibly with the right effect or outcome. This takes practice and oftentimes, forethought. Reflect and then react is often a statement I share with my students. Seiler and Beall (2011) conclude, “it isn’t the act or the amount of communication, but the content of communication that makes the difference.”

Words Contain Meaning

We have defined a symbol as anything that represents something else. Words are a representation of reality; they are not the things being represented, but are the codes we use for representation. The symbolic nature of words, therefore, indicates that they are labels we use to identify ideas and things for ease of reference, understanding and the sharing of meaning. Therefore, words inherently have no meaning. Thus, we can claim that meanings are not in words, but that they reside in people who created them for their own use. For example, where you live, snow may or may not be a normal part of your everyday lifestyle and function. Boas, is 1911, introduced a book that claimed that Eskimos possess dozens, if not perhaps hundreds, of different words for snow. Since they live, survive and utilize snow as a means of existence, words that represent ‘snow that is good for sledding’ (piegnartoq) or ‘snow that is softly falling’ (aqilokoq) allow them to function more effectively (Boas, 1911). Therefore, as we can now visualize through this example, words contain meaning to particular people for particular reasons.

Meaning is a personal experience though, and that is why we should further claim that no two individuals interpret the same experience the same way nor use words exactly the same way to mean the same thing. There are two general meanings of words: denotative and connotative. What a word denotes is not necessarily what it connotes. The denotative meaning of a word is its general, common, public meaning that you can find in a dictionary. But the real meanings of words are in their usage to convey the private, emotional, and unique, meanings of an individual. Therefore, the real meanings of words reside in the individual as expressed through its unique contextual reference.

Take the word “boyfriend” for example. The dictionary meaning would reference a male companion with whom one has a romantic or sexual relationship. Consider the case of two females who have a relationship with a male as a boyfriend. Each woman may have different connotations of the word boyfriend. One has a good boyfriend and describes him as “a great lover, supporter, dependable, and my best friend;” but the other woman does not share the sentiment of the first because of her different experience with her boyfriend. To her, the word boyfriend connotes “lazy, bum, irresponsible, son of a …” Meanings are in our heads via our perceptions and not in inanimate, abstract words. For more on connotative and denotative meanings, view the following:

Connotation and Denotation

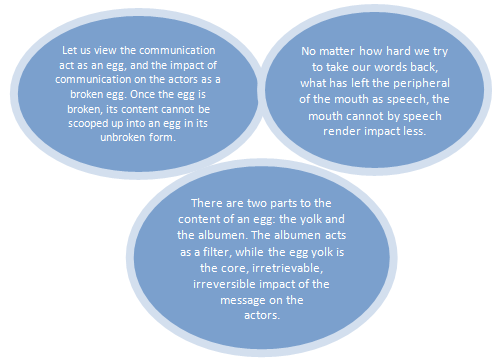

The Impact of Communication Is Reversible and Unrepeatable

Consider this – once an egg is broken or cracked, it cannot be reestablished. Further, once it is scrambled, you cannot poach the egg if you desired it to be cooked that way. As we have discussed earlier, communication has a consequence and such a consequence cannot be erased from the emotional memory of the receiver no matter how hard we try. So, however determined the attempt to take the impact of our words back, what has left our mouth as speech, cannot be retracted. It is imperative to understand that communication is irreversible and unrepeatable. We can apologize all of the live long day, but the apology does not retract the words. Therefore, be careful what you say and be mindful of how you say it to people so that you don’t have to “eat your words.”

Communication Is a Natural Human Ability

If you revisit the definitions we have for communication, you would realize that it is something we have to learn to do; it does not come to us as an inherent, innate human quality. An effective analogy would be talking versus communicating in a relationship. Learning to talk, or speak, barring any physiological complications, is an inherent, biological ability. However, effectively communicating with your parents, your partner or your best friend, is a different kind of ability. For it to be effective and positively feed the relationship, it must be done well. Therefore, we can see that communication is a learned skill just as leadership, baseball, or flying a plane. Just because you have a tennis racket in your garage does not make you a proficient tennis player. What would make you a good tennis player is the knowledge and the continued practice of the game. Only then will you become skilled.

The more you become familiar with the principles of communication and learn to apply them, even through the process of trial and error, the more you gain proficiency in the learned skill of communicating. As you learn to speak in various situations and put yourself in the public arena to perform, the more you would become familiar with what works and what does not in the art and practice of public speaking. Similarly, becoming a competent communicator requires gaining relevant knowledge of the principles and theories of communication. In addition, you must then have the willingness to translate your knowledge into practical skills that you will employ in your everyday communicative acts. Moreover, when performing these skills, at first, you may feel awkward, but with persistence, you will become proficient through repeated practice of the desirable skills. This is indeed the case with any skill you wish to succeed at. Consider that Tiger Woods, the professional golfer, replied to a fan that his practicing of golf equated to roughly 7-8 hours of daily practice (Kelley, 2016).

Figure 1.1. Impact of Communication on the Receiver

| Section 4 | Section 6 |